Introduction

If you want to learn anything faster and actually remember it a week later, you need to stop passive reading and start active teaching. I used to be the kind of student who would highlight every single sentence in a textbook. My book would look like a neon yellow coloring book by the end of the semester. I felt productive, but when I sat down for the exam, my mind would go blank. I recognized the words, but I didn’t understand the concepts.

This is a common trap called the “Illusion of Competence.” We mistake familiarity for mastery. It wasn’t until I stumbled upon a mental model used by a Nobel Prize-winning physicist that I realized I had been studying backwards.

The method is called the Feynman Technique. It is based on a simple truth: You don’t truly understand something until you can explain it in simple terms to a five-year-old. Since adopting this method, I’ve used it to master complex topics like video editing, economics, and even basic coding in half the time it used to take me.

In this deep-dive guide, I will walk you through the four steps of the Feynman Technique, the science behind why it works, and how you can use it to learn anything faster starting today.

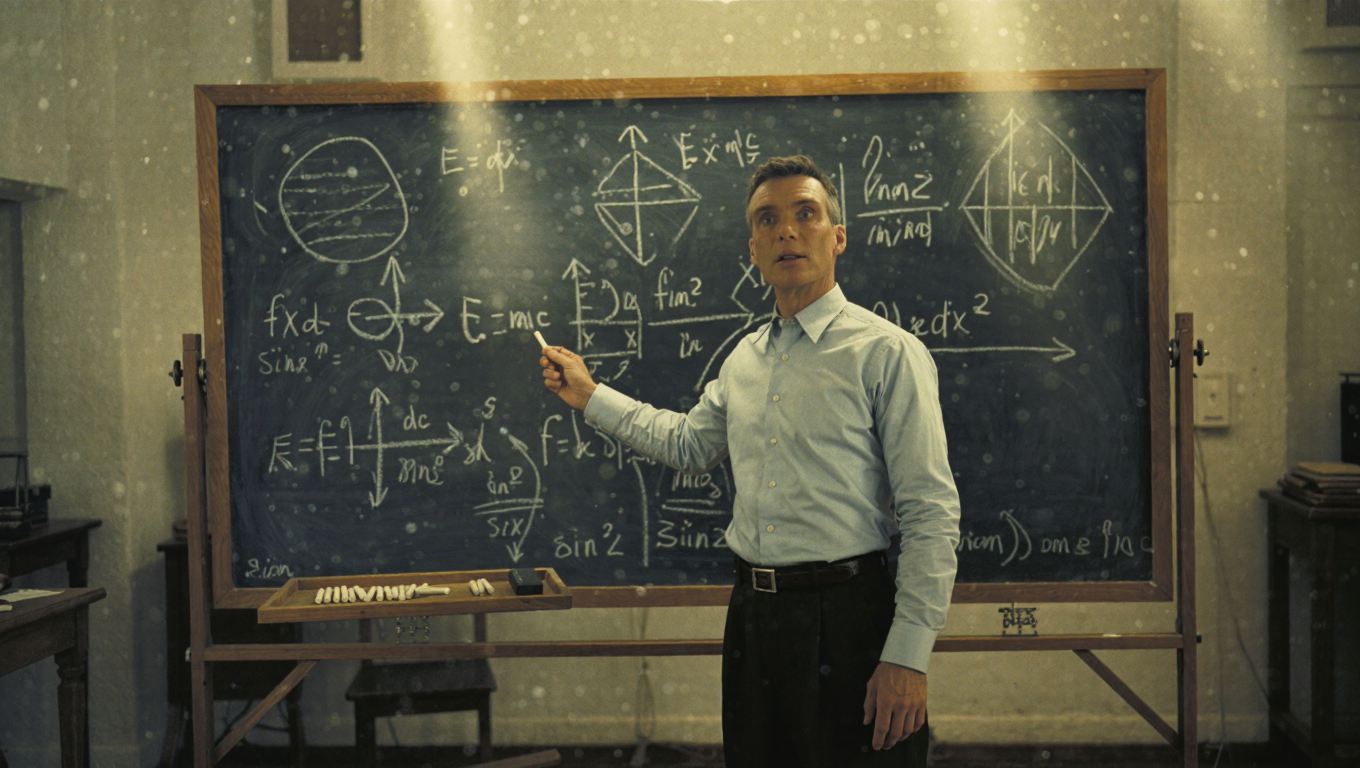

1. Who Was Richard Feynman? (The Great Explainer)

To understand the method, you have to understand the man. Richard Feynman was an American theoretical physicist who won the Nobel Prize in 1965. But he wasn’t just a genius; he was known as “The Great Explainer.”

Feynman despised jargon. He believed that complex vocabulary was often used to mask a lack of understanding. He famously said, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.”

While other professors confused their students with dense formulas, Feynman could explain quantum electrodynamics using simple diagrams and plain English. His philosophy was that simplicity is the ultimate form of sophistication. This philosophy is the core of how we learn anything faster and retain it forever.

2. The Science: The Protégé Effect

Why does explaining things help us learn? It turns out, there is hard science backing this up. It is called the Protégé Effect.

Studies have shown that students who expect to teach a material to someone else score higher on tests than students who expect only to be tested themselves. When your brain knows it has to transmit information, it organizes that data differently. It looks for connections, cause-and-effect relationships, and analogies.

Passive learning (reading/watching) is like collecting bricks. Active learning (teaching) is like building a wall. You can have a million bricks, but without the mortar of understanding, you don’t have a wall.

3. Step-by-Step: How to Use the Feynman Technique

The technique is deceptively simple, but don’t let that fool you. It consists of four distinct steps.

Step 1: Choose Your Concept Grab a blank sheet of paper. Write the name of the topic you want to learn at the top. It could be anything—”Black Holes,” “The French Revolution,” or “How a Blockchain Works.”

Step 2: Teach it to a Child This is the most critical step. Write down an explanation of the topic as if you were teaching it to a 12-year-old (or a 5-year-old, for extra difficulty).

-

Do not use jargon. Don’t say “mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell.” Explain what it actually does (e.g., “It acts like a battery that gives energy to the tiny parts of your body”).

-

Use analogies. Connecting the new concept to something familiar is the secret weapon to learn anything faster.

Step 3: Identify Your Gaps As you try to explain it simply, you will get stuck. You will realize, “Wait, I don’t actually know how the battery connects to the machine.” This is good! This is where the learning happens. When you stumble, go back to your source material (textbook, lecture, website). Re-read only the part you didn’t understand. This targeted learning is far more efficient than re-reading the whole chapter.

Step 4: Review and Simplify Now that you have filled the gaps, read your explanation out loud. Is it smooth? Is it simple? If you still sound like a textbook, simplify further. Create a narrative. Once you can tell the “story” of the concept without looking at your notes, you have mastered it.

4. The “Rubber Duck” Debugging Method

Programmers have used a version of the Feynman Technique for decades, called Rubber Duck Debugging.

When a coder is stuck on a bug, they explain their code, line-by-line, to a yellow rubber duck sitting on their desk. It sounds insane, but it works. By forcing themselves to verbalize the logic to an inanimate object, they often spot the error immediately.

You don’t need a human audience to use the Feynman Technique. You can talk to a rubber duck, your cat, or even a voice recorder. The act of speaking out loud is what forces the cognitive processing required to learn anything faster.

5. Digital Tools to Apply This Technique

While Feynman used a pen and paper, we have digital tools that can help.

-

Notion: I use Notion toggles. I write the question as the toggle header and the simple explanation inside. I test myself by trying to answer before opening the toggle.

-

Obsidian: Great for linking concepts together, mimicking how the brain connects ideas.

-

Loom: Record a 2-minute video of yourself explaining the topic. You don’t have to post it, but watching it back will show you exactly where you are confident and where you are faking it.

6. Why Simplicity is Power

We are often taught that big words make us sound smart. In reality, big words often hide confusion. Think about the smartest people you know. They usually explain things clearly, not confusingly.

-

Bad Explanation: “The market is experiencing a bearish downturn due to macroeconomic volatility.”

-

Feynman Explanation: “People are scared to buy stocks right now because everything is getting expensive, so the prices are dropping.”

The second one is actionable. The first one is noise. When you strip away the noise, you reveal the truth. That is how you learn anything faster.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Does this work for math and numbers? A: Absolutely. Instead of just memorizing the formula, explain why the formula works. For example, explain why Pi is 3.14 (it’s the ratio of the circle’s circumference to its diameter) rather than just memorizing the number.

Q: What if I don’t have time to write everything down? A: You can do it mentally, but it is less effective. Writing or speaking forces you to slow down and process. If you are in a rush, just try to explain the core concept out loud while driving or showering.

Q: Is this better than flashcards? A: Flashcards (like Anki) are for memorization. The Feynman Technique is for understanding. You should use the Feynman Technique first to understand the concept, and then use flashcards to memorize the details.

Q: Can I use AI like ChatGPT for this? A: Yes! A great prompt is: “I am going to explain [Topic] to you. Tell me where my explanation is wrong or confusing.” This turns the AI into your student.

Conclusion

The next time you are struggling to grasp a new concept, don’t re-read the page for the tenth time. Close the book. Imagine a child is sitting next to you, and try to explain it to them. You will struggle, you will stumble, but ultimately, you will understand. Mastery isn’t about hoarding complexity; it’s about revealing simplicity. That is the true secret of the Feynman Technique.