The relentless march of technological progress, particularly in the realms of virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and computational power, has ignited a fascinating and deeply unsettling question: Is it possible that our entire existence, every sensation, thought, and interaction, is merely a sophisticated simulation? This isn’t a new concept, finding echoes in ancient philosophical thought and science fiction, but the increasing sophistication of our own digital creations lends an eerie plausibility to the idea. The “simulation hypothesis,” famously articulated by philosopher Nick Bostrom, suggests that one of three propositions must be true: either civilizations almost always go extinct before becoming technologically mature enough to create realistic simulations, or technologically mature civilizations almost never choose to create such simulations, or we are almost certainly living in a computer simulation.

At its core, the simulation hypothesis hinges on the notion that if a civilization reaches a sufficiently advanced technological stage, capable of harnessing immense computational power, they would likely have the ability to create incredibly detailed, conscious simulations of their ancestors or alternative histories. Given the sheer number of potential simulated realities such a civilization could generate, the statistical probability suggests that any given conscious entity within one of these simulations is far more likely to be a simulated inhabitant than an original, “base reality” being. Imagine a future where our descendants possess the processing power of an entire galaxy. They could run billions of simulated universes, each populated by conscious beings. From the perspective of an individual within one of these simulations, their reality would feel perfectly authentic, indistinguishable from a “real” one.

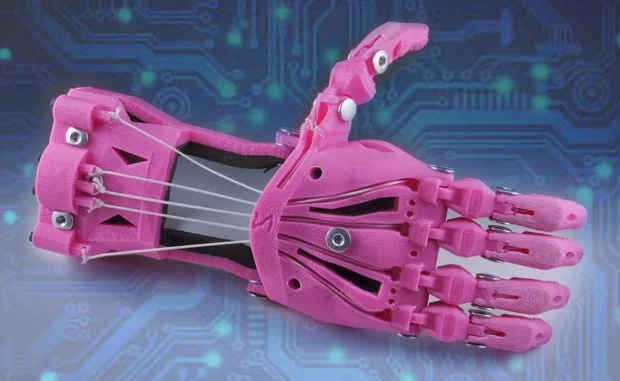

The escalating sophistication of our own virtual environments provides a compelling, albeit nascent, parallel. Think about the progression from pixelated video games to today’s hyper-realistic virtual reality experiences. Modern VR headsets can immerse users in environments that engage multiple senses, creating a profound sense of presence. As haptic feedback technology improves, as our understanding of brain-computer interfaces deepens, and as AI generates increasingly convincing virtual characters, the line between the physical and the digital blurs. If our current technological trajectory continues for centuries, or even millennia, it’s not a stretch to imagine a future where the virtual worlds we create become indistinguishable from our own perceived reality, complete with conscious, artificial inhabitants.

From a business perspective, the implications of even contemplating the simulation hypothesis are intriguing. It pushes the boundaries of innovation. Companies investing in virtual reality, augmented reality, and AI are, in a sense, building the rudimentary layers of what could one day become incredibly complex simulated environments. The pursuit of ever-more immersive digital experiences, driven by consumer demand and technological ambition, directly aligns with the capabilities presumed necessary for a “base reality” civilization to create our own. Moreover, the very act of pondering such a possibility encourages a critical examination of what we consider “real” and how our perceptions shape our decisions, a valuable exercise for any leader navigating uncertain futures.

However, despite its captivating nature, the simulation hypothesis faces significant challenges and criticisms. One immediate hurdle is the lack of empirical evidence. There is no demonstrable proof or verifiable anomaly within our perceived reality that definitively points to its simulated nature. Every observation we make, every scientific law we discover, appears to operate consistently within the framework of our physical universe. Furthermore, the computational demands for running a truly conscious, universe-sized simulation are astronomical, potentially exceeding the physical limits of even advanced civilizations. Would a “base reality” civilization truly dedicate such immense resources to running ancestor simulations, especially if the simulated beings became genuinely conscious and demanded rights or resources?

Philosophically, the hypothesis also raises questions about its testability. If our reality *is* a simulation, then any “glitches” or “anomalies” might simply be part of the simulation’s design, or too subtle for our simulated minds to detect. This makes it a difficult hypothesis to falsify, which is a cornerstone of scientific inquiry. Moreover, even if we were in a simulation, it doesn’t necessarily answer the ultimate question of existence; it merely pushes the problem up one level, begging the question of what the “base reality” is, and whether *it* is also a simulation.

Ultimately, while the idea that we might be living in a simulated reality is a compelling thought experiment, it remains just that – a hypothesis. It forces us to confront fundamental questions about consciousness, reality, and the future trajectory of technology. It highlights the exponential growth of computational power and the increasing sophistication of our own digital creations. While we may never definitively prove or disprove it, the very act of considering such a possibility fuels innovation, encourages philosophical introspection, and reminds us that our understanding of the universe, and our place within it, is constantly evolving. For now, the most pragmatic approach for individuals and businesses alike is to operate within the reality we perceive, focusing on tangible advancements and ethical considerations within the universe we can directly interact with and shape.